Gen Z and the Death of Britain

Brexit, the rise of Scottish, Irish and Welsh nationalism, and institutionalised racism has killed British identity. Nobody should be surprised.

A poll by The Times that found that “Half of Generation Z think that Britain is a racist country and only a tenth would risk their lives to defend it in a war” has sent section of the commentariat into a tailspin.

Shocked, The Times whines: “An authoritative study into the views and beliefs of Generation Z adults — those aged 18-27 — carried out with YouGov and Public First has revealed a deep erosion of faith in Britain.”

This has come as a deep shock to many who assumed that after decades of Tory-Labour rule, young people would be, somehow, miraculously, eager to die for King and Country and holding faith in the institutions of state that have presided over institutionalised racism, and believe in a country that has abandoned them as it’s split apart.

You can only think that these people haven’t been paying attention.

The survey revealed that:

Only 41 per cent of young people today were proud to be British and just 15 per cent believed the country was united

Almost half (48 per cent) of those aged 18 to 27 thought that Britain was a racist country, far more than the proportion who thought it was not

50 per cent believed that the UK was stuck in the past

Only 11 per cent would fight for Britain — and 41 per cent said there were no circumstances at all in which they would take up arms for their country

In Scotland, none of this comes as a surprise.

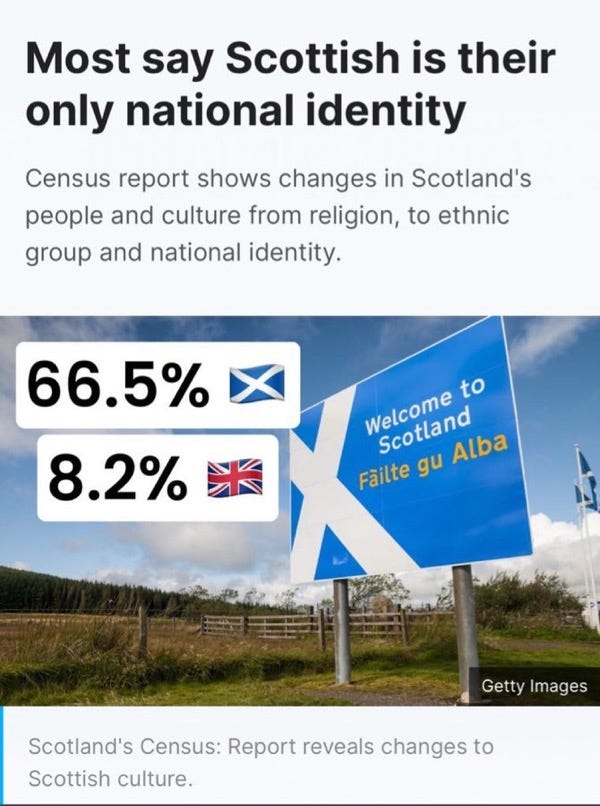

The 2024 Scottish Census gives the political/cultural context to The Times “shock poll” in Scotland, though I imagine the driving factors in England are quite different.

8.2%

The 2024 Scottish Census revealed that 66.5% of people identify themselves as Scottish and only 8.2% identify as British.

The report stated: “The percentage of people who said Scottish was their only national identity increased since the previous census (from 62.4% to 65.5%). The percentage who said their only national identity was British also increased (from 8.4% to 13.9%). The percentage who said they felt Scottish and British decreased (from 18.3% to 8.2%).”

This isn’t hugely surprising. For the past forty years there’s been a quiet revolution in cultural renewal with emergent institutions and structures to represent Scottish cultural life. It’s a process that is hugely flawed, incomplete and inadequate – especially in terms of broadcast and and media devolution; support for indigenous languages; investment in film and tv and theatre; and Scottish-based publishing and literature. I’ve explored these themes over and over for the past fifteen years and more. However, despite these failings, that are in part the result of not achieving sovereignty and in part the result of a failure of nerve and ambition within devolution, we have still seen a huge renewal of cultural confidence. People are far less ashamed of their own culture, feel it has worth and are able to both value it and critique it. We are minus key institutions to reinforce this huge change, but we are miles away from the sort of cultural cringe that used to dominate and undermine our cultural lives.

So 66.5% isn’t going anywhere and the trajectory is only going North. What this means politically is a different matter. Jim Sillars famous accusation of ’90 Minute Patriots’ may still hold clear, or more so 80 minute ones. There is a performative aspect to proclaimed Scottish identity that might have no political outcome than wearing your kilt at Murrayfield.

But in the long-term these things do matter. It is not surprising that after decades of decline and shame and shambles people don’t want to be associated with Britain or British identity. When I was a child the Union Jack was seen everywhere, other than a brief spell with Geri Halliwell and then with Cool Britannia it has gone – only to be associated with the far-right or enclaves of loyalism. It’s there when there’s a state occasion – another jubilee – coronation – death – birth – but its ubiquity and power as a unifying symbol has not survived.

It’s interesting to note that the percentage who said their only national identity was British also increased (from 8.4% to 13.9%). This could be a hardening of British identity by those who feel under ‘threat’, or that they wish to display their British Unionism. Or it could be people relocating from England who identify as ‘British’.

Perhaps more worrying for those who realise that British identity is wrapped-up with political choice, the census tells us that those who feel “Scottish and British” fell from about 1 in 5 to about 1 in 12.

That’s a disappearing generation and a disappearing identity. That’s not coming back. What this points to is the fact that feeling “Scottish and British” increasingly feels either impossible or unattractive or both. It suggests that there is a choice: increasingly you have to choose to be Scottish or British, the two notions are incompatible. You may rage against this, you may claim that its not impossible and it’s not unattractive but the data as laid out is pretty clear. A decrease of the percentage of people who felt Scottish and British from 18.3% to 8.2% is huge.

There’s an up and a downside to all this ‘Scottishness’. I want the political agency of self-determination. I want to live in a Scottish democracy. I don’t want my / our identity to be a substitute for that. It may be that this 65.5% continues to grow and it becomes an agent of change, a quite assumption with real-world political consequences. Why would someone who considered themselves Scottish not want Scotland to be a fully-functioning independent state?

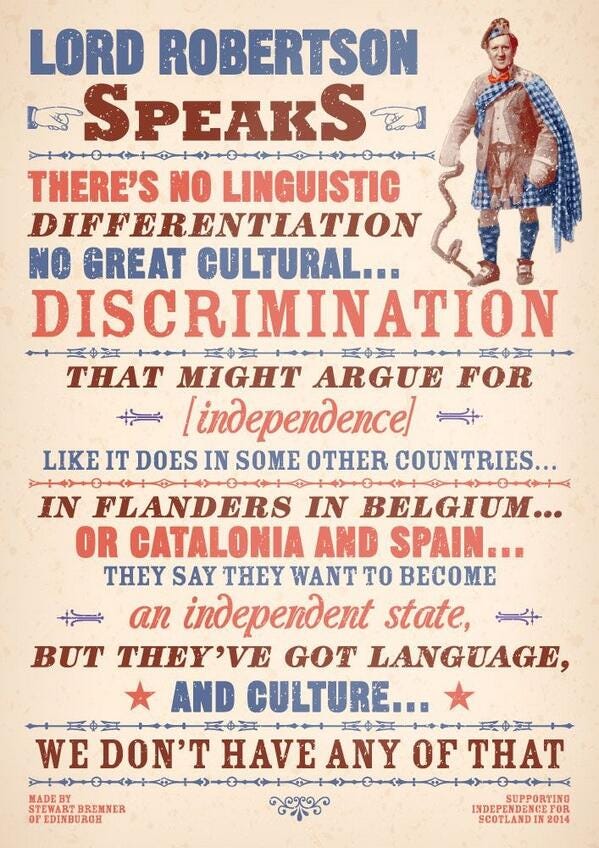

If you have been raised to be – unconsciously – ashamed of your own culture – unable to speak or write in your own language – finding your accent embarrassing – or assuming that your culture was either of no value or non existent – then how on earth would you possibly think you could run your own country? The high-point of this mode of cultural self-hatred may have been Lord George Robertson’s intervention in 2014, when he publicly decried the very idea that Scotland has ANY discernible language or culture. But to say something like that now would be met with incredulity outwith the circles of very strange group of people that rage against the use of Gaelic or Scots or any expression of Scottish identity.

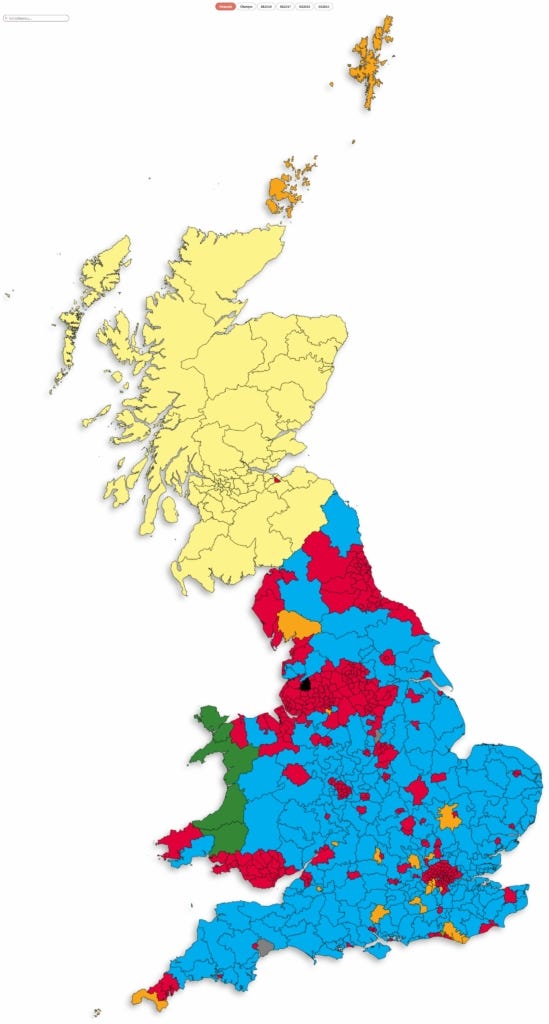

Why has British identity collapsed in Scotland? The Conservative governments did much to hasten this process, literally selling off all of the institutions and infrastructure that you might cling on to as in any way ‘British’. Secondly the Queen is dead and the whole surround of goodwill and association (much of it entirely unfounded) died with her. The generation of people who associate the Queen with an era of time from the 1940s and 50s, a time of Victory and renewal, a time we might have been proud of and might have been unified in, has gone. Third the experience of Brexit has accelerated the experience of difference, the stark reminder that Scots consider themselves Europeans and many people in England perceive Europe as a ‘threat’ reinforces the idea that the very concept of ‘Britain’ as a thing to discuss is disappearing.

Fourthly, as Gordon Brown never stops explaining to us, Britain is a land where a quarter of our children live below the poverty line.

Finally, the efforts to coerce people into a British identity or polity is so crass (see below) and so tone deaf that it backfires massively. This is not to say that there won’t be efforts in the future to ‘unite’ people around Britishness (people still go on about the London Olympics opening ceremony) and Labour are draped in the Union Jack, but as an identity that people in Scotland would cleave to, it’s completely dead.

If Brexit was billed as an attempt to project a ‘Global Britain’ it has failed spectacularly. Despite (or because) of the grotesque rhetoric from Boris Johnson and his colleagues post-Brexit Britain seems a harsher, crueler place as people are handcuffed and deported to Rwanda, as the John Woodcock report emerges, as the latest ‘scandal‘ unfolds. Starmer’s government has done little to change any of that.

Living on the outskirts of Anglo-Britain’s wreckage, viewed from the Celtic Fringe, Britain has been a memefest of indulgence in hyper-nostalgia for the last decade, the new version of Spitfire Nationalism allows you to hurtle even further back. Scattered among the poppies and the royals and the endless remembrance is a recurring meme carefully cultivated by the Leave leadership, that of conflating Brexit – and specifically No Deal Brexit – with “our finest hour”. In this landscape it’s no wonder that Britishness has died.

Nice piece Mike, and it's really great to have you on Substack. As someone living in Scotland since 1991 I consider myself Scottish, and supported independence. It's been great to see the retreat of cultural cringe, even though the version of Scots identity that culture often celebrates is decidedly middle class, and snobbery about working class or 'ned' culture remains, as Gavin F Brewis and Darren McGarvey have written.

As an artist who doesn't write about Scotland or Scottish identity, who is nonetheless based in Scotland, I often feel alienated by the tendency in the arts to focus solely on identity, nationality and nostalgia for the past. Do you think that Scotland's attempts to move on from cultural cringe risks a too overt focus on Scottish identities which can then be codified, commodified, and which become as oppressive in their narrow definitions as the cringe they replaced?

This is a big risk, and I imagine it might be even more keenly felt as exclusionary by those who live in Scotland, but still honour a different culture or traditions. In reclaiming Scottish identity have we made it too narrow? Might it become as tight and ill-fitting a suit for many Scots as 'British' has become for so many English people?

I'd like to see a Scottish media abd arts culture that celebrates us as a modern, diverse and multicultural society, where nationalism is more informed by civic pride and shared values rather than idealised, nationalist versions of the past and future, with no vision or ability to see the *present*.

Thanks for giving me lots to think about!